Harvest Levels

Timber Harvest Levels Tell a Striking Story

By Charlie Levesque

Everyone in the forest products industry in the northern US – from the Lakes States to Maine – knows that significant changes have been taking place over the last 10 to 20 years. Among them are transformations in the supply chain, a reduced and aging logging and trucking workforce, the loss of low-grade markets, and the ups and downs experienced by those producing solid wood products from logs. While great changes have always been a constant in the forest products industry, recent deviations will greatly impact younger people – owners of logging and trucking companies and mills, and their employees in the coming years.

Perhaps the most important metric for weighing changes in the supply chain over time is the most basic one: How much timber is being harvested each year? While some timber harvested in the region is shipped in log form to distant markets, the vast majority stays in the region for manufacturing of wood products at resident mills.

Available data helps us understand how the changes in the supply chain – such as reduction in workforce – have affected harvest levels and/or, how market changes have affected the supply chain.

Some states collect these data diligently and some states rely on broader public data sets – like the USDA Forest Service Timber Product Output (TPO) and Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) data collection systems – to provide year-to-year harvest levels data. Here, we rely on both major data sources.

Timber Harvesting Data Trends (Northern US)

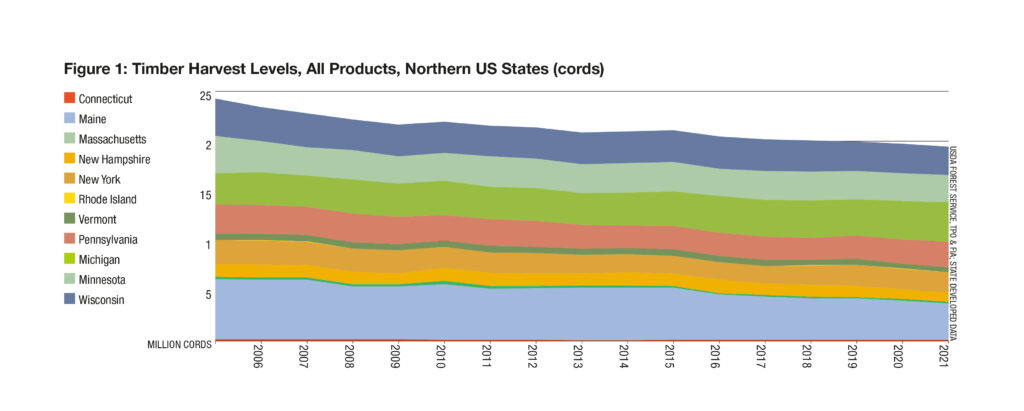

The best snapshot of trends in harvest levels can be seen in the 2005-2021 combined graph in Figure 1, which includes the 11 states we studied: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin. It would be ideal to compare the last 20 years, but this is the best available with consistent datasets among the 11 states. We dig deeper and include additional years for those states that have the data later in this article.

These data show a clear trend over all states: timber harvest levels have been decreasing each year for some time. Maybe this is a no-brainer as anyone in the business can point to one or more large wood-using plants that have closed over the last 15 years, no matter where they live in the 11-state region. Very few new mills have opened in that same time period.

The big question, however, is: Which is the dog, which is the tail, and which is running the show? Is the reduction in logging and trucking causing reduced harvest levels over time, or are reduced markets resulting in contracting demand for timber? It is important to say that in each of these states, FIA data clearly shows that standing forest volume is growing in every state, year after year, because net annual timber growth exceeds removals. In some states, a lot more. Connecticut and Massachusetts forests grow over 5 times more timber volume annually than harvest removals. This suggests it is not a reduction in standing timber that is causing reduced harvest levels. The FIA data does not get at the question of whether landowners are reducing the availability of their timber simply because they have decided not to harvest. Anecdotally, for many reasons (including selling carbon), we are seeing an increase in landowner reticence to harvesting.

Over the 17-year period, among the 11 states, these data show that there has been a 20% reduction in annual harvest levels – quite a significant decrease.

A Finer Analysis

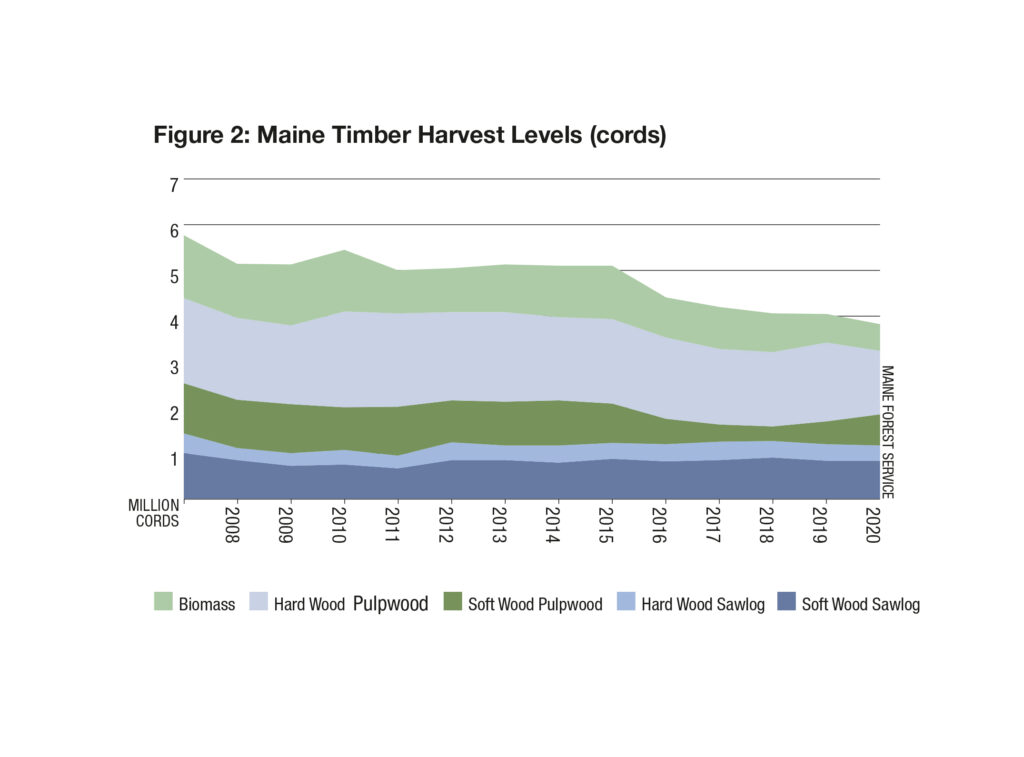

Looking at the 11-state region as a whole, this seems to be a serious trend – and it is. But what is happening with regard to the different products that are harvested each year? Fortunately, a few states have robust locally collected data on timber harvest levels that dig deeper into the products and species harvested each year.

For this, we have chosen Maine and New Hampshire, both of which collect their own timber harvest data.

For Maine, the overall timber harvest trend (Figure 2) is also down. A reduction in hardwood and softwood pulpwood harvest levels, along with biomass for energy, are the biggest trends these Maine data show. This may not be surprising to those in Maine, as multiple pulp mill and biomass plant closures occurred during this period. Overall harvest levels in Maine from 2007 to 2020 are down 34% in total, a rather significant decrease. Important to note is that sawlog harvest levels have stayed relatively steady for Maine and New Hampshire over the data period.

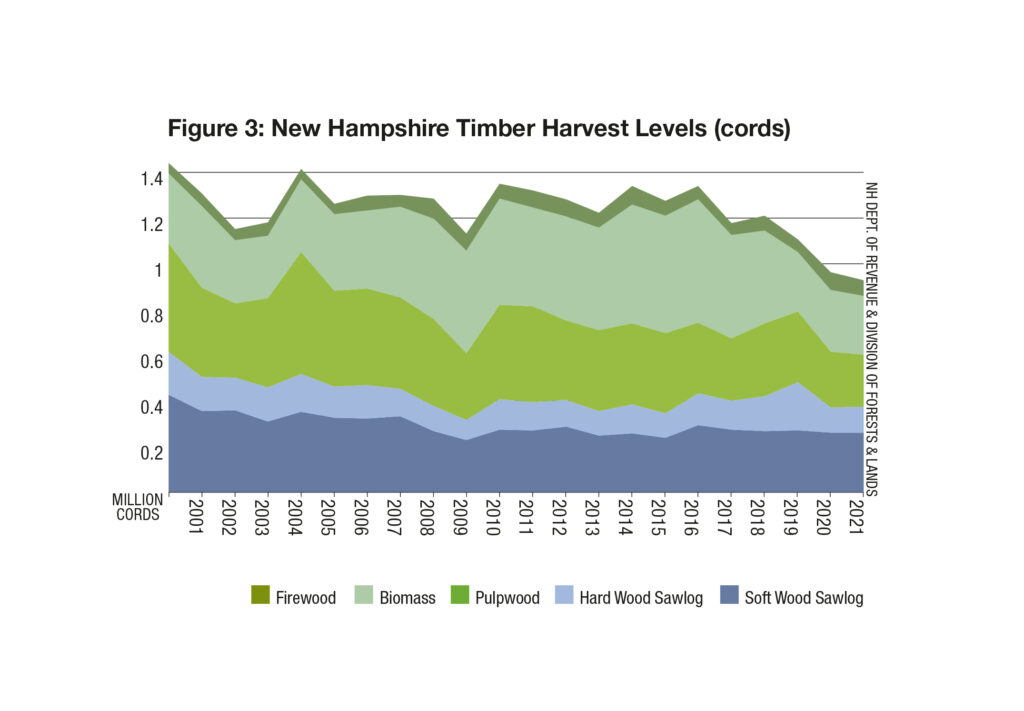

In New Hampshire (Figure 3), the wild fluctuations in harvest levels and the ultimate 35% reduction from 2000 to 2021 are also largely the result of pulpwood but, more so, biomass reductions as the biomass electricity plants have shut down or curtailed operations due to electricity market conditions and pricing.

In New Hampshire (Figure 3), the wild fluctuations in harvest levels and the ultimate 35% reduction from 2000 to 2021 are also largely the result of pulpwood but, more so, biomass reductions as the biomass electricity plants have shut down or curtailed operations due to electricity market conditions and pricing.

Recently, the Burgess biomass plant in Berlin, NH, the largest biomass plant in the 11-state region at 75 megawatts and using upwards of 800,000 tons of biomass wood fuel per year, has filed for bankruptcy. Can it operate after Chapter 11 proceedings are complete? If not, the New Hampshire harvest data for low-grade (and surrounding Vermont and Western Maine) will drop precipitously.

Lakes States vs. Northeast

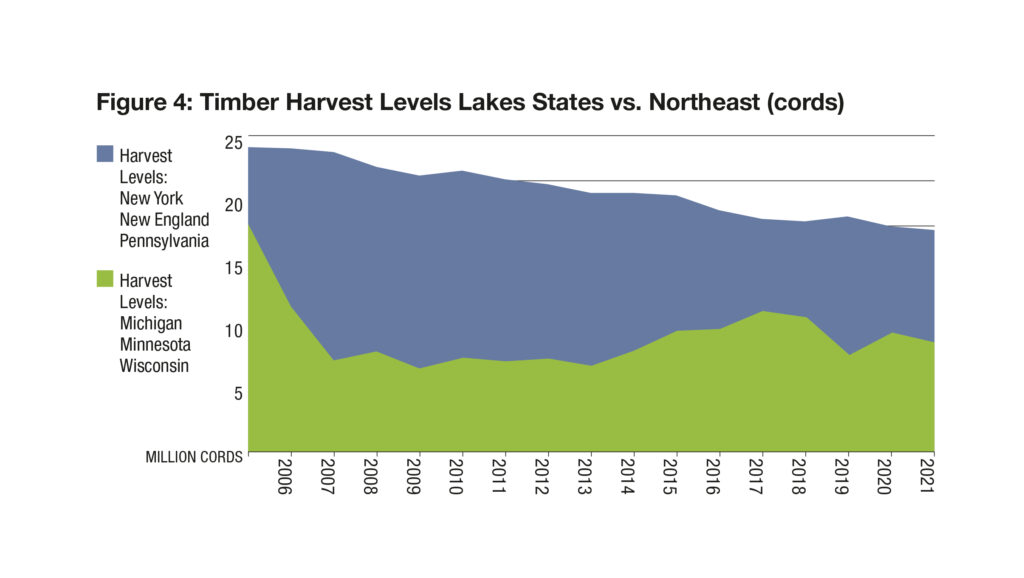

The Lake States and New England/New York/Pennsylvania regions have many differences but also some similarities. Analysis of the timber harvesting data (Figure 4) shows that the Lakes States saw a significant drop in harvest levels back around 2005-2008 from pulp mill closures and have stayed relatively stable (even increased a bit) from those lower levels to near present day.

In the Northeast, the drop has been much more steady over time with pulp mill and biomass electricity plants dropping off during the whole period.

What About Carbon?

While some would suggest that forest carbon markets are to blame for some of these changes, that simply isn’t true – yet. Will there be a mega-shift to selling forest carbon instead of timber over this wide geography at levels that would alter the data we have shown here? Time will tell, but this author believes the price of forest carbon offset credits will need to rise significantly – double or more than the current prices – to make a real difference.

Will Harvest Levels Continue to Decline?

Forest products market changes in the last 15-20 years are at the heart of reduced harvest levels. In particular, reductions in low-grade pulp and biomass for electricity markets have largely been the cause. Aging workforce and dwindling supply chain infrastructure in the logging and trucking sectors may be the result of these reductions in harvests. In the past, when a forest products market existed that paid enough and was steady enough, the key in-woods industry supply chain sectors of loggers and truckers always rose to the occasion to meet that market demand. Given the state of decline for low-grade markets in the region and the small scale of new market prospects relative to biomass plants’ and pulp and paper’s previous demand, the trend for reduced harvest levels will continue. The aging and reduced workforce in the in-woods logging and trucking sectors further exacerbates this likely future trend.

Charles Levesque is President of the northeast-based consulting firm Innovative Natural Resource Solutions, LLC. He can be reached at levesque@inrsllc.com and www.inrsllc.com.